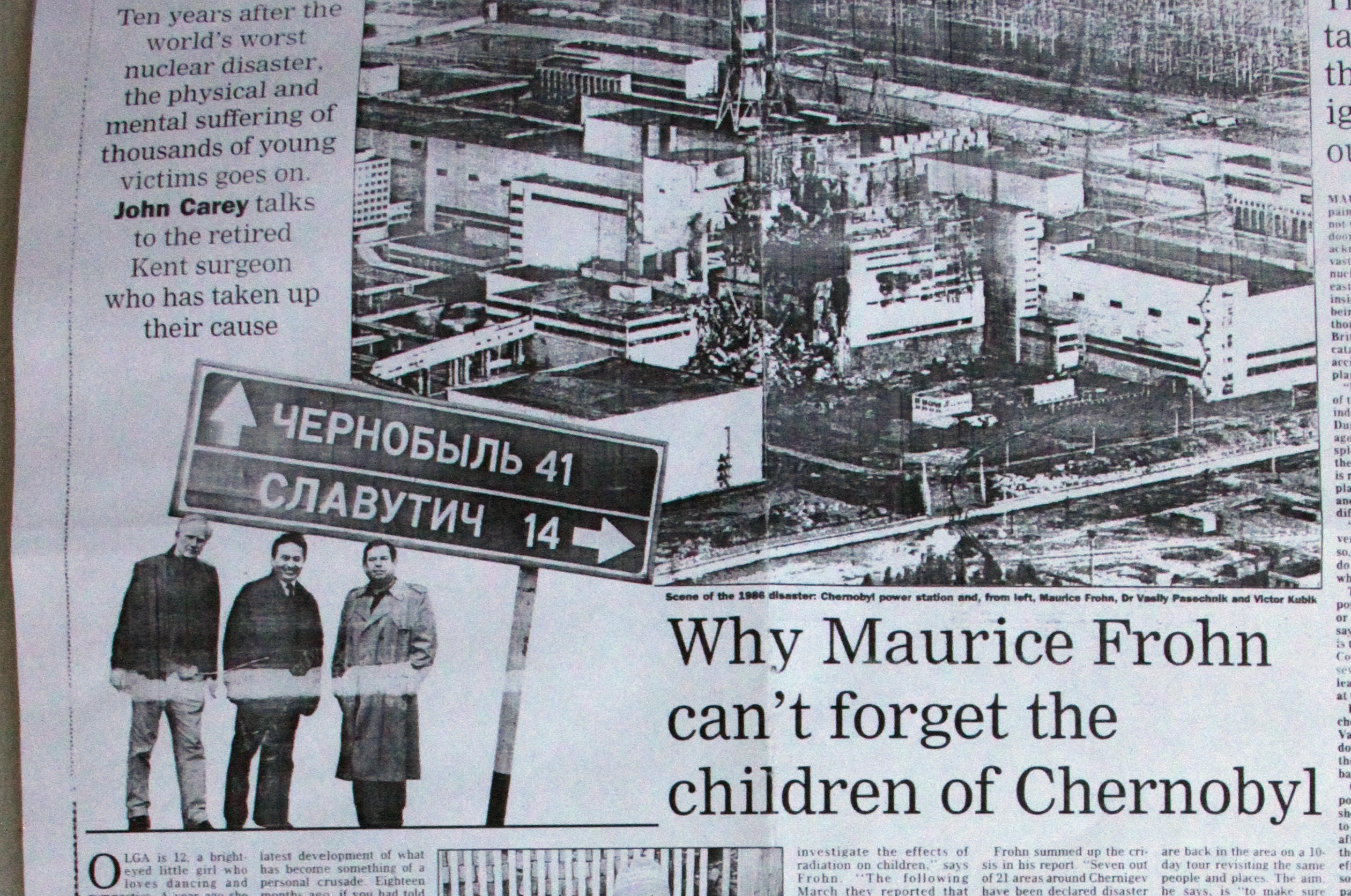

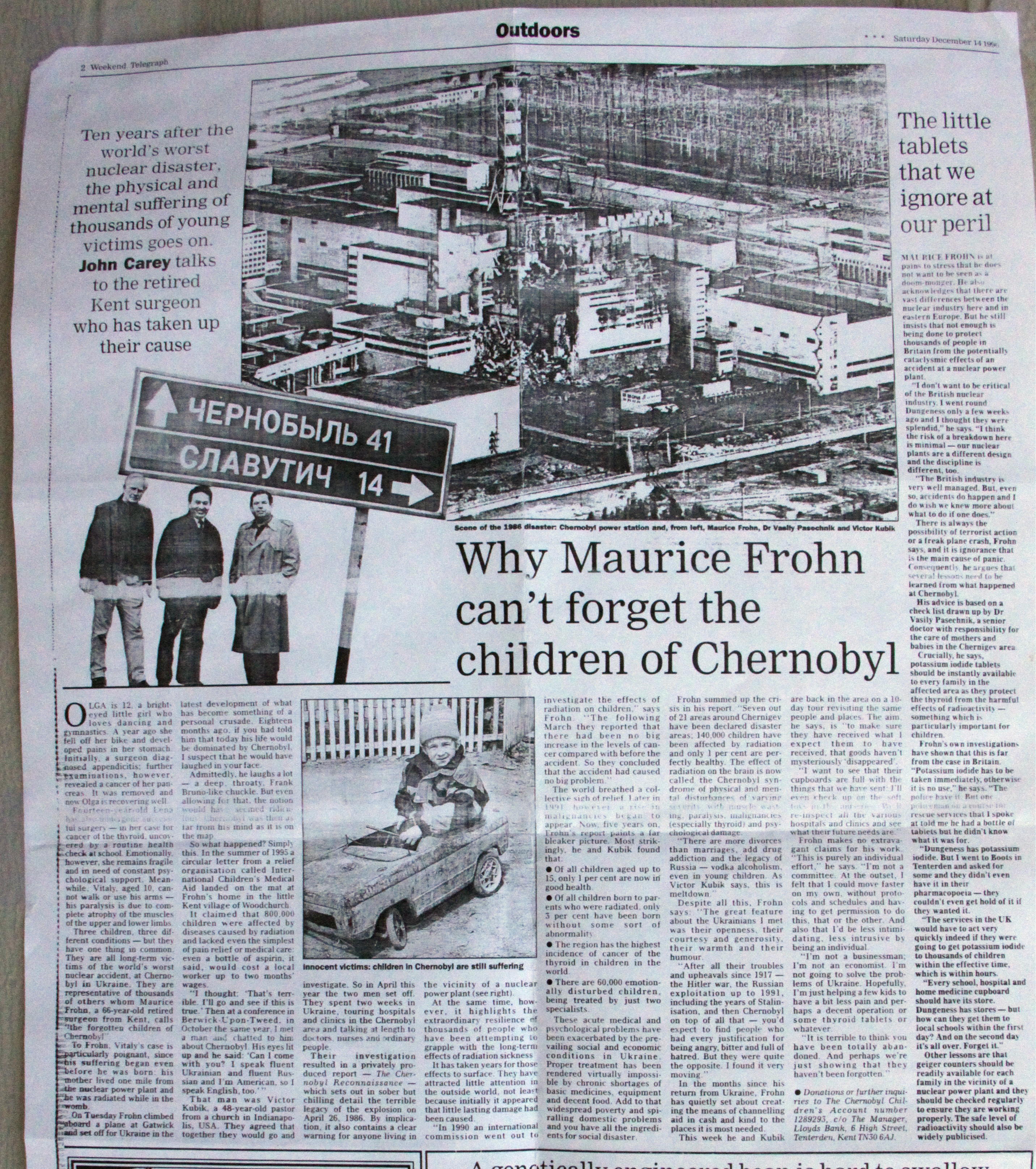

We have been working in the Chernobyl, Ukraine area since 1995 when I met Maurice Frohn, one of the most significant people in my life. We met in the United Kingdom in October 1995 and in a conversation that included his career as a surgeon working with thyroid cancer, pediatrics and gynecology and my Ukrainian background and knowledge of the Ukrainian and Russian languages we set off on three visits to the Chernobyl area from April 1996 to December 1997. Maurice Frohn set up the Chernobyl Children's Trust shortly thereafter I started LifeNets in 1999. The London Daily Telegraph did a full page story about Maurice Frohn on December 14, 1996 in their weekend edition. More about our work in Chernobyl at https://lifenets.org/chernobyl.

Clearer and more readable PDF's below:

- The London Daily Telegraph December 14, 1996

- Why Maurice Frohn can't forget the children of Chernobyl

- The little tablets that we ignore at our peril

London Daily Telegraph December 14, 1996

Why Maurice Frohn Can’t Forget the Children of Chernobyl

(From the Weekend Telegraph, Saturday, December 14, 1996)

Olga is 12, a bright-eyed little girl who loves dancing and gymnastics. A year ago she fell off her bike and developed pains in her stomach. Initially, a surgeon diagnosed appendicitis; further examinations, however, revealed a cancer of her pancreas. It was removed and now Olga is recovering well.

Fourteen-year-old Lena has also undergone successful surgery-in her case for cancer of the thyroid, uncovered by a routine health check at school. Emotionally, however, she remains fragile and in need of constant psychological support. Meanwhile, Vitaly, aged 10, cannot walk or use his arms – his paralysis is due to complete atrophy of the muscles of the upper and lower limbs.

Three children, three different conditions – but they have one thing in common. They are all long-term victims of the world’s worst nuclear accident, at Chernobyl in Ukraine. They are representative of thousands of others whom Maurice Frohn, a 66-year-old retired surgeon from Kent, calls “the forgotten children of Chernobyl”.

To Frohn, Vitaly’s case is particularly poignant, since his suffering began even before he was born: his mother lived one mile from the nuclear power plant and he was radiated while in the womb.

On Tuesday Frohn climbed aboard a plane at Gatwick and set off for Ukraine in the latest development of what has become something of a personal crusade. Eighteen months ago, if you had told him that today his life would be dominated by Chernobyl, I suspect that he would have laughed in your face.

Admittedly, he laughs a lot – a deep, throaty, Frank Bruno-like chuckle. But even allowing for that, the notion would have seemed ridiculous. Chernobyl was then as far from his mind as it is on the map.

So what happened? Simply this. In the summer of 1995 a circular letter from a relief organization called International Children’s Medical Aid landed on the mat at the Frohn’s home in the little Kent village of Woodchurch.

It claimed that 800,000 children were affected by diseases caused by radiation and lacked even the simplest of pain relief or medical care: even a bottle of aspirin, it said, would cost a local worker up to two months’ wages.

“I thought: ‘That’s terrible. I’ll go and see if this is true.’ Then at a conference in Berwick-Upon-Tweed, in October the same year, I met a man and chatted to him about Chernobyl. His eyes lit up and he said: ‘Can I come with you? I speak fluent Ukrainian and fluent Russian and I’m American, so I speak English, too,’”

That man was Victor Kubik, a 48-year-old pastor from a church in Indianapolis, USA. They agreed that together they would go and investigate. So in April this year the two men set off. They spent two weeks in Ukraine, touring hospitals and clinics in the Chernobyl area and talking at length to doctors, nurses and ordinary people.

Their investigation resulted in a privately produced report – The Chernobyl Reconnaissance – which sets out in sober but chilling detail the terrible legacy of the explosion on April 26, 1986. By implication, it also contains a clear warning for anyone living in the vicinity of a nuclear power plant (see right).

At the same time, however, it highlights the extraordinary resilience of thousands of people who have been attempting to grapple with the long-term effects of radiation sickness.

It has taken years for those effects to surface. They have attracted little attention in the outside world, not least because initially it appeared that little lasting damage had been caused.

“In 1990 an international commission went out to investigate the effects of radiation on children,” says Frohn. “The following March they reported that there had been no big increase in the levels of cancer compared with before the accident. So they concluded that the accident had caused no big problem.”

The world breathed a collective sigh of relief. Later in 1991, however, a rise in malignancies began to appear. Now, five years on, Frohn’s report paints a far bleaker picture. Most strikingly, he and Kubik found that:

- Of all children aged up to 15, only 1 percent are now in good health

- Of all children born to parents wo were radiated, only 3 percent have been born without some sort of abnormality

- The region has the highest incidence of cancer of the thyroid in children in the world.

- There are 60,000 emotionally disturbed children, being treated by just two specialists.

These acute medical and psychological problems have been exacerbated by the prevailing social and economic conditions in Ukraine. Proper treatment has been rendered virtually impossible by chronic shortages of basic medicines, equipment and decent food. Add to that widespread poverty and spiraling domestic problems and you have all the ingredients for social disaster.

Frohn summed up the crisis in his report. “Seven out of 21 areas around Chernigev have been declared disaster areas; 140,000 children have been affected by radiation and only 1 percent are perfectly healthy. The effect of radiation on the brain is now called the Chernobyl syndrome of physical and mental disturbances of varying severity, with muscle wasting, paralysis, malignancies (especially thyroid) and psychological damage.

“There are more divorces than marriages. Add drug addiction and the legacy of Russia – vodka alcoholism, even in young children. As Victor Kubik says, this is meltdown.”

Despite all this, Frohn says: “The great feature about the Ukrainians I met was their openness, their courtesy and generosity, their warmth and their humour.

“After all their troubles and upheavals since 1917 – the Hitler war, the Russian exploitation up to 1991, including the years of Stalinisation, and then Chernobyl on top of all that – you’d expect to find people who had every justification for being angry, bitter and full of hatred. But they were quite the opposite. I found it very moving.”

In the months since his return from Ukraine, Frohn has quietly set about creating the means of channeling aid in cash and kind to the places it is most needed.

This week he and Kubik are back in the area on a 10-day tour revisiting the same people and places. The aim, he says, is “to make sure they have received what I expect them to have received, that goods haven’t mysteriously ‘disappeared’.

“I want to see that their cupboards are full with the things that we have sent: I’ll even check up on the soft toys in the nurseries. We’ll re-inspect all the various hospitals and clinics and see what their future needs are.”

Frohn makes no extravagant claims for his work. “This is purely an individual effort,” he says. “I’m not a committee. At the outset, I felt that I could move faster on my own, without protocols and schedules and having to get permission to do this, that or the other. And also that I’d be less intimidating, less intrusive by being an individual.

“I’m not a businessman; I’m not an economist. I’m not going to solve the probmes of Ukraine. Hopefully, I’m just helping a few kids to have a bit less pain and perhaps a decent operation or some thyroid tablets or whatever.

“It is terrible to think you have been totally abandoned. And perhaps we’re just showing that they haven’t been forgotten.”

Inset: Ten years after the world’s worst nuclear disaster, the physical and mental suffering of thousands of young victims goes on. John Carey talks to the retired Kent surgeon who has taken up their cause.

The Little Tablets That We Ignore at Our Peril

(From the Weekend Telegraph, Saturday, December 14, 1996)

Maurice Frohn is at pains to stress that he does not want to be seen as a doom-monger. He also acknowledges that there are vast differences between the nuclear industry here and in Eastern Europe. But he still insists that not enough is being done to protect thousands of people in Britain from the potentially cataclysmic effects of an accident at a nuclear power plant.

“I don’t want to be critical of the British nuclear industry. I went round Dungeness only a few weeks ago and I thought they were splendid,” he says. “I think the risk of a breakdown here is minimal – our nuclear plants are a different design and the discipline is different, too.

“The British industry is very well managed. But, even so, accidents do happen and I do wish we knew more about what to do if one does.”

There is always the possibility of terrorist action or a freak plane crash, Frohn says, and it is ignorance that is the main cause of panic. Consequently, he argues that several lessons need to be learned from what happened at Chernobyl.

His advice is based on a check list drawn up by Dr. Vasily Pasechnik, a senior doctor with responsibility for the care of mothers and babies in the Chernigev area.

Crucially, he says, potassium iodide tablets should be instantly available to every family in the affected area as they protect the thyroid form the harmful effects of radioactivity – something which is particularly important for children.

Frohn’s own investigations have shown that this is far from the case in Britain. “Potassium iodide has to be taken immediately, otherwise it is no use,” he says. “The police have it. But one policeman on a course for rescue services that I spoke at told me he had a bottle of tablets but he didn’t know what it was for.

“Dungeness has potassium iodide. But I went to Boots in Tenterden and asked for some and they didn’t even have it in their pharmacopoeia – they couldn’t even get hold of it if they wanted it.

“The services in the UK would have to act very quickly indeed if they were going to get potassium iodide to thousands of children within the effective time, which is within hours.

“Every school, hospital and home medicine cupboard should have its store. Dungeness has stores – but how can they get them to local schools within the first day? And on the second day, it’s all over. Forget it.”

Other lessons are that Geiger counters should be readily available for each family in the vicinity of a nuclear power plant and they should be checked regularly to ensure they are working properly. The safe level of radioactivity should also be widely publicized.